You signed in with another tab or window. Reload to refresh your session.You signed out in another tab or window. Reload to refresh your session.You switched accounts on another tab or window. Reload to refresh your session.Dismiss alert

Copy file name to clipboardExpand all lines: README.md

+7-7Lines changed: 7 additions & 7 deletions

Display the source diff

Display the rich diff

Original file line number

Diff line number

Diff line change

@@ -12,19 +12,19 @@ Here we'll give just a brief description of the core ideas around the mapper, bu

12

12

13

13

1. Take any *lens* you want. A lens is just a continuous map $f \colon X \to Y$, where $Y$ is any parameter space, usually having dimension lower than $X$. You can think of $f$ as a set of KPIs, or features of particular interest for the domain of study. Some common choices for $f$ are *statistics* (of any order), *projections*, *entropy*, *density*, *eccentricity*, and so forth.

2. Build an *open cover* for $f(X)$. An open cover is a collection of open sets (like open balls, or open intervals) whose union makes the whole image $f(X)$, and can possibly intersect.

3. For each element $U$ of the open cover of $f(X)$, let $f^{-1}(U)$ be the preimage of $U$ under $f$. Then the collection of all the $f^{-1}(U)$'s makes an open cover of $X$. At this point, split every preimage $f^{-1}(U)$ into clusters, by running any chosen *clustering* algorithm, and keep track of all the local clusters obtained. All these local clusters together make a *refined open cover* for $X$.

4. Build the mapper graph $G$ by taking a node for each local cluster, and by drawing an edge between two nodes whenever their corresponding local clusters intersect.

N.B.: The choice of the lens $f$ has a deep practical impact on the mapper graph. Theoretically, if clusters were able to perfectly identify connected components (and if they were "reasonably well behaved"), chosing any $f$ would give the same mapper graph (see the [Nerve Theorem](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nerve_complex#Nerve_theorems) for a more precise statement). In this case, there would be no need for a tool like the mapper, since clustering algorithms would provide a complete tool to understand the shape of data. Unfortunately, clustering algorithms are not that good. Think for example about the case of $f$ being a constant function: in this case computing the mapper graph would be equivalent to performing clustering on the whole dataset. For this reason a good choice for $f$ would be any continuous map which is somewhat *sensible* to data: the more sublevel sets are apart, the higher the chance of a good local clustering.

67

+

68

68

69

69

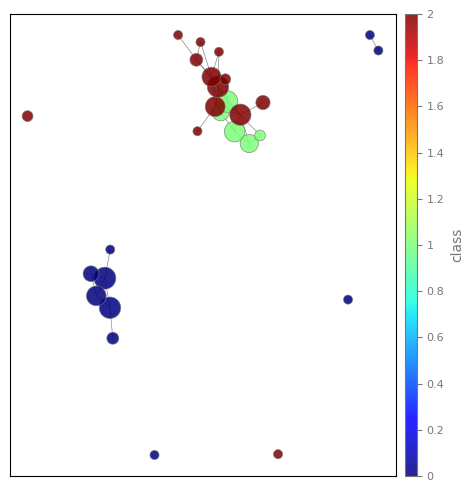

As you can see from the plot, we can identify two major connected components, one which corresponds precisely to a single class, and the other which is shared by the other two classes.

99

+

100

100

101

101

As you can see the mapper graph shows interesting patterns. Note that the shape of the graph is obtained by looking only at the 8x8 pictures, discarding any information about the actual label (the digit). You can see that those local clusters which share the same labels are located in the same area of the graph. This tells you (as you would expect) that the labelling is *compatible with the shape of data*.

102

102

103

-

103

+

104

104

105

105

Moreover, by zooming in, you can see that some clusters are located next to others. For example in the picture you can see the details of digits '4' (cyan) and '7' (red) being located one next to the other.

0 commit comments